| The Courier - N°159 - Sept- Oct 1996 Dossier Investing in People Country Reports: Mali ; Western Samoa հղում աղբյուրինec159e.htm |

| Country report |

|

|

Country report

Mali : An omnipresent sense of history

Some countries have a strong folk memory. Despite its size, Mali appears hemmed in by its frontiers. For more than a thousand years, this state was a splendid empire, constantly spreading outward and reflecting the history of the African continent with its conquests and alliances, reversals of fortune and moments of glory. At its height, it extended from the Atlantic to the Sudanese border, from the south of Morocco to the north of Nigeria. Mali's history rests in the minds of its people rather than in any structures inherited from the past. This acts as an antidote to the 'amnesia' often brought on by colonisation, which has the effect of paralysing the future. Although poor, the country has a well-established sense of its place in the world.

A racial melting pot

`

On the eve of colonisation, Mali was known es 'west Sudan'. In 1924, the territory then known as 'French Sudan' was split up and small portions of the Malian nation were incorporated into the seven states bordering it-a move certainly not calculated to have a cohesive effect on the remnants of the old empire. Mali has long been a melting pot of races, ethnic groups and cultures. They have learned to live together- intermingling, sometimes forming unexpected alliances, and occasionally fighting one another. The result today is a potpourri where true racial or ethnic confrontation is difficult to imagine. The interplay of history and the mixing of ethnic groups, families and individuals, has created what one intellectual de scribed to us as 'the anti Rwanda vaccine'. Historical mythology offers, perhaps, further evidence of the fusion of cultures in this country. As in ancient Greece or Rome, to take European examples, each ethnic group and each Malian empire, was 'backed' by a host of gods, spirits and totems. In this nebulous world, where dreams beget history and where vastly differing ethnic groups can trace themselves back to a common ancestor, the result was a multiplicity of interrelationships. Under various names, the python totem belongs to many different peoples, including the Peal, Ma/inke and Sarakolle. A study of the migrations of the peoples who make up Mali also reveals a great many relationships - for example, between the Dogon, who are black, and the Shongoi; who are more half-caste. They regard one another as cousins, originating from Aswan in Egypt.

Malians appear to share a genuine sense of belonging in keeping with their shared culture. The 'people' of Mali came into being long before the state of the same name. The guerilla war fought in recent years by the Tuaregs (this is the English plural, Tuareg already being the plural form of Targul) against the Malian army, is often viewed abroad as a struggle between whites (or Arabs) and blacks. But this is an illusion. Although the Tuaregs are probably the only 'white' minority in the country, they are an integral ingredient in the melting pot. They are also known as 'Kel-Tamasheq' - those who speak Tamashek, which was originally the language of their Bella slaves. Like all the country's ethnic groups, they have dominated and have in turn been dominated. They have forged alliances with one another, and, more commonly, have united against Arab or Berber invasions. The relative absence of bitterness overall is probably due to the fact that each of Mali's peoples has had its era of glory and imperial dominance.

Mali is lucky to have such knowledge of its history. For centuries, the most precise details have been collected by the griots. The same role has also been played by the many secret societies which have initiation periods lasting, in some cases, up to 50 years. They were, and sometimes still are, repositories for the secrets of history, magic, astrology and science, and also for the symbols of power-the religious objects and artefacts of the former emperors. There are written sources as well, something which is quite rare in Africa. These have been transcribed since the beginning of the millennium and, in recent decades, close collaboration between historians, griots and members of traditional societies has enabled a deeper knowledge to be gained of Mali's history.

A rich empire

Asselar Man, discovered near Timbuktu in the centre of Mali, was a contemporary of Cro Magnon Man.

Cave paintings from five thousand B.C. reveal similarities with those in Egypt and are probably the work of migrant populations from the east, who moved into Mali as the Sahara Desert expanded. Less reliable sources state that interbred populations of Jews and Egyptians under the command of an officer of the Pharaoh Dinga created the Soninke dynasty (originating from Aswan). These people probably laid the found ations of the first great Malian empire, that of Ouagadou. Other sources, equally unreliable, report that they were probably Judaeo-Syrians who arrived at the end of the third century A.D. and found a population already in place. What is more or less certain is that, during the first millennium, a Soninke dynasty was installed around the current frontier between Mauritania and Mali and that 40 princes ruled it in succession in the period prior to 750 A.D. Initially, these rulers were white but, with increasing intermarriage, their skins became darker and darker. To Arab chroniclers, Mali came to be known as Bafour or Bilad es-Soudan (the country of the blacks). At the beginning of the second millennium, the Ouagadou empire held sway over several kingdoms in the south, including the Nigerian delta and a number of Berber principalities. Documents dating from this period have replaced the name Ouagadou with that of Ghana, by analogy, perhaps, with the emperor's title. The empire was already very rich, the richest in the world according to an Arab chronicler who visited it in 970. A work by the writer A/ Bakri, which appeared a century later (1087) went into great detail about the empire's organisation-the system of matrilinear succession, the role of councils of dignitaries, and the capital, Koumbi (whose foundations were discovered in 1914 in southern Mauritania). This city was divided into two districts, one of these being the sacred, imperial city, home to the empire's python totem to which a young girl was sacrificed every year.

A story of courage

The killing of the snake totem is the most significant myths in the country's history. The hero of the story is Amadou Sefedokete whose love for his beautiful fiancee Sia (who was about to be offered in sacrifice), prompted him to descend into the monster's lair and confront it. By killing the totem, he broke the thread of countless generations before him, who had carried out the ritual sacrifice. He is still remembered for this magnificent action, based on love and a sense of nobility, and he remains a subject for artists of all types. His brave action still causes young lovers in Africa to shudder in admiration. However, this act of deicide brought about a reversal of fortunes. The monster's seven heads, which the young hero is said to have cut off one after the other, are reputed to have been scattered to the four comers of the earth, thereby dispersing the empire's riches and leaving it penniless. The true story is more prosaic. Ghana's wealth was eyed greedily by the Arabs and Berbers who had long traded with it. The empire's resistance in the face of Islam gave Moroccan religious fanatics a pretext for organising a jihad. It was invaded by an army of 30000 devotees supported by forces from some of the empire's black vassal states. The 'holy war' began in 1042 ending 34 years later with the occupation of Koumbi.

The occupation did not last long but was followed by internal clan wars which brought about the end of an era. Restoration came about at the end of the 72th century , in the small Sosso kingdom, south of Ouagadou (also set up by a small group of Soninké). One of the minor kings called Soumangourou Diarasso dreamed of recreating Ghana's empire, and, in 1203, he succeeded in sacking the ancient capital of Koumbi in a move designed to establish his own dynasty. This was an important symbolic act and in the fierce war which followed, Soumangourou subjugated Mandé, a region which was overflowing with wealth. One of Africa's greatest heroes, Soundjata, rose up against him. He was supposedly the legitimate heir to the Mandingo throne, but was unable to walk, having been born an invalid of a deformed mother who had been married at the recommendation of the king's sorcerer. His young half-brother took his place on the throne and sent the paralysed prince into exile. At the age of 18, Soundjata decided to seize his own place in history and a 'giant' was thus bom. In 1235, his army fought that of the bloodthirsty Sosso monarch whom he himself is said to have cut down in an extraordinary battle. It was a fight which, according to the legends, saw the use of all types of weapon, including magic. Soundjata had forged a grand alliance in order to gain victory. Rather than reducing to vassalage the small kingdoms which had allied themselves with him, the new emperor decided to form them into a federation-although he wisely declared that from Niani (his capital), 'I shall see all'. His empire took the name of 'Mali' (the hippopotamus) on account of that animal's strength and mastery of bath water and land. For 20 years, the empire was to stretch as far as the Atlantic Ocean. Its structure, based on a number of warrior clans, craftsmen, freemen and marabous, is still characteristic of Mali and neighbouring countries today. The empire was rich in gold once again but also in terms of agricultural organisation with the development of cotton and groundout farming. Soundjata disappeared mysteriously in 1255, leaving a prosperous empire.

'Conquest' of America?

In 1285, there was a struggle for succession between two princes and a third, Prince Sakoura (a freed slave), took advantage of the quarrel to take power for himself. Sakoura expanded the empire by subjugating the Timbuktu Tuaregs and the Gao Shongoi: After his short reign, a genuine heir of Soundjata, Aboubakar II, ascended the throne. He had his eye on conquests over the seas and, according to the story, he set sail westwards leading a fleet of 2000 vessels. He was never seen again. However, recent studies favour the hypothesis that he was not lost at sea as had always been supposed' but did, in fact, reach the Americas. A series of ineffective monarchs succeeded this 'conqueror of the impossible', who preceded Christopher Columbus by 200 years, leaving little real impression on history other than the records of their exuberant behaviour. One of them, for example, went on a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 with a reported retinue of 60 000 and distributed considerable amounts of gold to all the dignitaries he encountered in that holy place. These kings, however, are acknowledged as having preserved the empire's unity, guaranteeing order without repression and allowing wide religious, moral and sexual tolerance, even for married women.

The kingdom centred on Gao dates back to at least the first millennium but it was usually a vassal of the Ouagadou empire and of Mali. One of its kings, Sonny Ali Ber (known as Sonny the Great), came to the throne in 1464, profiting from the decay of the Mali empire. His reign was marked by a bitter struggle against the Ulémas of Timbuktu who, over a period of four centuries following the Almoravid conquest, had converted a large portion of the empire to Islam. The circumstances of Sonny's disappearance are uncertain, but he is thought to have drowned in 1492, the year when a certain Genoese navigator was to achieve the ancient goal of 'discovering' the Malian empire.

Sonny Ber's successor did not last long in the face of Islamic expansion. The new Askia dynasty was installed to lead the Shongoi empire, and this expanded with the annexation of Dahomey and part of Nigeria. However, a small part of the former Mali empire never passed under their rule. The Askia dynasty blew hot and cold in terms of religious fervour. Tyrannical at first, it later took a softer line. Under the reign of one monarch, the Gao court based in the university city of Timbuktu became a place of exceptional refinement-only to slide once again into a state of intolerance. One of the Askias, having destroyed the last symbols of the former Mali empire, the city of Niani, set upon his former Moroccan allies. Another emperor, Askia Daoud (1549-1582), turned out to be a fine administrator. He developed agriculture and set up a genuine bank in Gaol War with Morocco continued throughout his reign and beyond. In 1584, imperial force defeated 20 000 Moroccan soldiers, winning a victory which might have been decisive had it not been for internal dissent. This weakened the Askia side and enabled Morocco, with a band of Spanish mercenaries, to take over the empire, following a battle in April 1591. Success was due, above all on this occasion, to the firearms deployed by the winning side. Such weapons were unknown to the 45 000 Malian cavalry and infantry who were engaged. It also turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory. The occupying troops sent the great scholars from Timbuktu University to Morocco, where their peers took up their cause. Moreover, the foreign soldiers were won over by the easy life in Mali-and one of the first results of their presence was a big increase in the half-caste population. In 1612, the troops rejected the Moroccan command: the occupation was at an end and the last few Moroccans were later expelled from Timbuktu by the Tuaregs.

Black religious proselytism and colonisation

To each dog his day. In the 17th century, the Bambaras set up an empire around Segou, but the debauched lifestyle of several of the sovereigns and disapproval of the part they played in the slave trade proved to be their downfall. Once again, the history of the country was to be shaped by a slave- Ngolo Diarra-who founded his dynasty in 1766. He was able to restore a degree of prestige to the kingdom, but his efforts were undermined after his death. As a reaction, a proselytising Black Islam then began to evolve.

Massina became a theocratic state around the beginning of the 19th century, in common with other kingdoms which appeared at the same time. One of their most famous rulers, the conqueror El Hadj Oumar, was defeated by the troops of the French General Faidherbe who forced him to give up West Senegal. The days of Malian independence were now numbered. The courage of his successor only delayed the progress of French colonisation, which finally prevailed at the end of the century.

Resistance fighters carried on the war from other points in the old empire, particularly from what is now Guinea. The country was dismantled by the colonial system and pacified, but the end of the Second World War and the return of African soldiers brought a renewed desire for independence. French Sudan became the rallying point for freedom fighters in the French colonies-the old dream of reunification was not dead and buried. In 1946, the Rassemblement Democratique Africain was set up, later to become the USRDA (Union soudanaise-Rassemblement democratique africain). In 1956, the future architect of Mali's independence, Modibo Keita, was appointed leader of the movement and elected to represent the 'Sudan' in the French Assembly. A 'Malian Federation' project was drawn up to include Dahomey (Benin), Upper Volta (Burkina Faso), Senegal and 'Sudan' (Mali). A constituent assembly of independence movement representatives was set up in 1959. However, the constitution adopted by the local Malian and Senegalese assemblies was rejected by the other two. The Federation now had only two members but was nonetheless proclaimed independent on 20 June 1960. In the event, the spirit of unity was lacking and, on the pretext of a rivalry between the two leaders (the 'Sudanese' Modibo Keita and the Senegalese Mamadou Dia), Senegal withdrew from the union in August. On 22 September 1960, the 'Sudan', now without an outlet to the sea, adopted one of the most prestigious names in its history: Mali.

The new state was landlocked not only geographically but also, very soon, politically. Modibo Keita's socialist agenda prompted foreign investors to pull out, and the country was organised increasingly as a 'people's democracy'. Fortunately, the repression was not excessive but a sizeable proportion of the population disapproved of the system that had been chosen. Mali and Guinea still had modest aspirations to their old dream of unification. The founder of the Republic, Modibo Keita, was overthrown by a military coup on 19 November 1968. More than the break-up by colonisation, which left dreams of Sudan being reconstituted, this military putsch sounded the knell of the old empire. Mali became just another state whose colonial and post-colonial eras have been marked by a lack of success. Nevertheless, a sense of history is still omnipresent.

Hegel Goueier

Three republics to create one democracy

It is just something you have to get used to-in French-speaking Africa, virtually all countries have imitated France in assigning a number to each republic formed under a new constitution. At the time of its independence on 20 June 1960, Mali was a federation of two states; Senegal and the former 'French Sudan'. It was an alliance which failed after only a few weeks'existence end 'French Sudan' then adopted one of its most prestigious former names- Mali.

The first regime, under Modibo Keita, became increasingly unpopular as its form of 'tropical' marxism caused it to become more and more isolated. One of its main shortcomings was its unrealistic five-year plans, none of which were ever implemented. Discontent became rife among various social groups. including the farmers who, opposed collectivisation and were adept at passive resistance which they employed to disrupt the supply of produce. The regime also modelled itself on the so-called 'people's democracies' in certain respects. For instance, it made a determined effort to improve education, health and social justice, while refraining from the more dictatorial excesses that often characterised such systems.

Initially welcomed by some sections of the population, the November 1968 putsch, by Lieutenant Moussa Traore quickly fumed into dictatorship although it was to be more than 10 years before there were any significant anti-government protests. At the end of 1990, opponents of the regime openly set up organisations which claimed opposition-party status. One of these was ADEMA (the Alliance for Democracy in Mali), formed by the current President of the Republic, Alpha Oumar Konare. Marches calling for a multi-party state attracted the support of tens of thousands of people.

The dictator then sought to neutralise the opposition, beginning with the Tuaregs in the north who had been waging a guerilla war. This conflict was viewed by many as the 'front line' in the people's struggle against dictatorship, and the Tuareg cause was supported by opposition movements. The government, which had for some time opted for 'soft' repression, now revealed its claws and in January 1991 it began to imprison student leaders. The streets were filled with armoured vehicles and the first death amongst the students brought condemnation. Repression reached its height on 22 March 1991, when several dozen students were killed.

Prior to this, in February 1991, Moussa Traore's UDPM (Democratic Union of the Malian People) came out in support of a multi-party system - a move which marked the beginning of the end of the regime. The day after the students were killed, a democracy coordination committee launched an appeal for a general strike, to last until the dictator was overthrown. This began on 26 March, and amounted, in effect, to a 'democratic' coup d'etat. Its instigator was Lieutenant Colonel Amadou Toumani Toure, who took charge of the transition to-tether with the democratic movements.

The former dictator was arrested and put on trial for his crimes. He was later condemned to death but his sentence was recently commuted by President Konare.

The Tuareg guerilla war continued despite the government's conciliatory attitude. The new administration also had to deal with a number of social claims which had long been stifled by the dictatorship. However, popular support for the regime remained firm. The new constitution was adopted virtually unanimously in a January 1992 referendum and, a week later, ADEMA won the municipal elections, the first in a series of electoral victories for Alpha Oumar Konare. He went on to win the Presidential election (for the Third Republic) in April, with almost 70% of the vote. Meanwhile, negotiations with the Tuareg rebels resulted only in signatures on agreements which were not observed. The situation grew worse with the Ghanda Koy counter-offensive, but this in turn led to a seemingly viable accord between the Azawad Arab Islamic front, the most important guerilla movement, and the Malian government. Last March, President Konare presided over an enormous bonfire of weapons seized from the former guerilla fighters. The flames lit up the skies above Timbuktoo, the symbol par excellence of rapprochement between the peoples of Mali.

At the beginning of January 1994, the regime suffered the effects of the devaluation of the CFA franc. Economic liberalisation had enabled Mali to improve its macroeconomic position, but social discontent, particularly in the towns and cities, demonstrated that the average citizen was continuing to suffer economic hardship. The President still enjoys considerable support, and political democracy is greatly appreciated. Obviously, the government cannot be blamed for all the difficulties facing the country. There is, for example, a lack of professionalism in the press. However, it could have given a lead in the case of the State media, which still studiously avoids criticising the government's actions. The administration has also been taken to task for its apparently lax attitude towards 'economic' misdemeanours.

Next year will see a series of elections. The government views these with apprehension, although it has stolen a march over its rivals by signing a political accord with several small parties. Opposition is centred around the MPR (Patriotic Movement for Renewal), the revamped former party of the dictator Moussa Traore. This has undergone a 'facelift, and now seems to be regaining support. lts trump card is decentralisation. Its former leaders, who held total power for a quarter of a century, can take advantage of the network of contacts they built up. The US-ADA, the party of the Republic's founder, Modibo Keita, which until recently appeared to be the herald of change, seems lately to have restricted its role to that of arbiter. Surprises are in the offing, but one thing is certain: the Third Republic's constitution will remain the guarantee of democracy in Mali.

H.G.

Interview with Ali N. Diallo, President of the National Assembly

In Mali, the army has learnt if from the past

Mali's institutions were radically remodelled in the wake of the recent vote on decentralisation. This is aimed at allowing, among other things, a degree of autonomy for the north of the country-which is essential to guarantee national reconciliation. The sudden growth in the number of small towns and villages may result in some political surprises during the long e/ection campaign period which is due to begin early next year. The President of the National Assembly, Ali N. Diallo, finds himself in a pivotal position: his Adema (A/fiance for Democracy in Mali) party current/y holds a comfortable majority in Parliament. With democracy being consolidated in Mali, he must find this an exhilarating time. Our frst question touched on this

-This is certainly an excellent time to be in Mali, but freedom is the most difficult of man's needs to satisfy. Our National Assembly has 12 parties and most people in our country are inspired by ideas based on tolerance and respect for the right to be different. The main concern of those of us who lead the party currently in the majority, is to question constantly whether we are necessarily always right. We have a comfortable majority-72 members out of 115-but this certainly doesn't mean that the National Assembly is just a rubber stamp.

· There is, of course, another stumbling block when one has such a large majority, which is the possibility of internal divisions.

-Yes, I would agree with you there. Mali's MPs have to realise that they came into this business after a three-stage process. First there was a popular uprising, then the army intervened to put an end to the bloodbath.

Finally, we had the high level national conference to draft the constitution, the electoral code and the charter for the country's parties. MPs, therefore, must always bear in mind that, though they can claim legitimacy on the basis of the revolution, there is also a republican legitimacy they ought to respect.

· The second phase in the process was the intervention of the army-are you not a*aid that the 'Niger syndrome'will raise its ugly head in Mali, too ?

- Naturally, MPs have seen what happened in Niger and elsewhere, but fear is tempered here because officers in Mali's forces have also given a great deal of thought to the effects of military dictatorship. Democrats and republicans within the armed forces are very aware that only a minority of men in uniform profited to any degree from the previous regime.

· Do you think that because Mali had what might be called a 'moderate' dictatorship, it is now in a better position than it would have been had the previous administration been more repressive ?

-Let me put it this way. The military dictatorship went through three different stages. During the first stage, just after the coup on 19 November 1968, the junta chose Mao Tse Tung as a model, hammering home the idea that power could be won by force of arms-and it was carried away by the popular acclaim it initially received. Subsequent popular resistance then took them by surprise. People wanted more freedom, but they also wanted to keep what they had gained in social matters. Army officers asked the protestors to abandon their action so that normal constitutional life could be resumed, but the trade unions had their own ideas. They advocated things which the people in power opposed. The ensuing repression was therefore fierce.

There was a second phase during which the military were at odds with one another over the leadership question. The popular view was that the country had fourteen different heads of state at that time. This went on until 28 February 1978 when there was a brief Iuli and they were tempted to return power to the civil authorities.

Then came the third phase when, despite appearances, poverty was on the increase. At first, Malians said that there were two 'IMFs' on the loose in Mali-the International Monetary Fund and the intimate circle surrounding the Moussa family. When the social foundation of the regime contracted, and all the country's business became concentrated in the hands of Moussa, his wife and her relations, the popular forces went on the offensive. This was a period of vociferous protest. Moussa Traore reacted with brutality: hence the 200 dead amongst the schoolchildren and students who were protesting- we will never know the exact number.

· Yet, the former regime could be said to have made the crucial economic choices which your government has continued with.

-I wouldn't agree with that. There was a half-hearted discussion at the time about liberalising the economy but, in reality, bureaucracy got in the way. It is the economic laws voted in by ourselves which form the true basis of a liberal economy. However, if you really want to look to the past, I would say that it was the February 1967 accords signed between Mali and France, when we came back into the franc zone, which set the whole process rolling.

· The Tuaregs and the government have just signed an agreement but the question of the north of the country is still a sensitive one. What are your views on this subject ?

-The problem in the north of Mali is extremely complex. First, the Malian nation is made up of a patchwork of minorities, the largest being the Ban Mana (Ed. 'Bambara' in the colonial vocabulary), but no ethnic group is larger than all the others put together. Second, all groups have, at one time or another, held supremacy. But the fact is that the peoples involved have all lived in the same area throughout history- they have shared joys and sorrows, and their blood has mingled on Malian soil. l would accept that the Malian nation is not as well consolidated as it should be, but it is arguably one of the most advanced in the sub-region in terms of its constitution-though I don't mean to sound chauvinistic here.

Anyway, the problem in the north of the country seems to me to be one of development. The various regions have not all developed at the same rate on account of climate differences. In addition, the dictatorship did not show any great respect for minorities - although it did not direct its actions solely against the Tuaregs, who resorted to arms. The Tuaregs exaggerated the mistreatment they had suffered because they were unfamiliar with what was happening in the rest of the country. In fact, Moussa Traore oppressed everyone: the French-style Jacobin state we inherited did not allow for regional differences. After independence, the regime redoubled its efforts to centralise the state. both because it was Jacobin in outlook and because of Modibo Keita's communist leanings. In 1959, the French forced the Tamashek (ea. 'Tuaregs') to secede-Max Lejeune and Houphouet Boigny were mixed up in all that. This was when oil was first discovered in Algeria and the war with Algeria had been in full swing since 1954. Modibo Keita set up the Malian Federation and declared in 1959 that, upon independence, he would withdraw all soldiers from the Algerian front. Since the Malian Federation was dismantled, Gao virtually became an Algerian willaya, a base camp for its fighters. Mali did not accept this. Moreover, Algeria, around the time it achieved independence, took retaliatory measures and sealed off its borders, mercilessly sending back huge numbers of refugees. It mobilised them through humiliation, telling them that they were the last members of the white race-the only ones to allow themselves to be under black rule.

· But when Ganda Koy's militia halted the Tuareg movement, they appeared to have been supported by the black population. Doesn't that also suggest a racist attitude ?

-I addressed the Tuaregs in October 1992, and pointed out that their wish to regard themselves as overlords and the other peoples in Mali as vassals who ought to pay tribute would provoke a general uprising, with the risk of a slide into civil war. I told several of the Tuareg chiefs seated around me the legend of Ouagadou- about the serpent of the well who each year demanded that the Soninke people should sacrifice an 18-year-old girl in its honour. Then the day came when a young man refused to accept the sacrifice of his fiancee. He went down into the monster's lair, watched by a horrified crowd who saw his recklessness as folly, and cut off the serpent's head. In the beginning, the Malian people's sympathies in fact lay with the rebellion. On 26 March, when the rebellion against the dictatorship took place, the president at the time, Konare, asked for all the Tuareg chiefs to be brought to him so that they could set up a transition body. He got a nasty surprise when the Tuaregs resorted to arms.

· Was the government, as rumoured, behind the Ganda Koy ?

-Not the government as such. To my mind, it would be wrong to applaud when one faction of the people one governs wants to exterminate another faction.

· It appears that some of the people are unhappy with the concessions that have been made to the Tuaregs.

-This is a myth. The idea that we are frustrated because the Tuaregs were once our masters, is a story put about by Europe. The situation is quite the reverse. At the time of colonisation, they were unwilling to ream, like other nomads, such as the Peul people, for example. There were splits with them, of course, but no actual, all-out war. Forging a nation always requires tears, sweat and mourning. Those who return will find what they left broken or stolen and will want land which is less barren than that impoverished by the encroaching desert. However, those who stayed put in the face of rebel attacks had their houses smashed and their animals taken away. There will be problems when some Peals, for example, identify their cows which were stolen. We will have to negotiate, but I have confidence in the people. Just as they ended the war, they will be able to heal the wounds-of this I am sure. And the process has already started.

· I gather that you continue to practice as a doctor, on top of your political duties. Is this to teach a moral lesson to your political colleagues ?

-I would say that it is more of a weakness, an inability to abandon a passion, even for supposedly good reasons. l am an 'internalist' and I have a passion for mechanisms. If you cure an infection and it returns, you have to look elsewhere to solve the problem. There are those in authority who spend money on trying to tackle problems without troubling to locate the cause. I would like to think that the analytical rigour of clinical science might also be put to good use in promoting understanding in politics.

Profile

General information

Area: 1 240 190 km²

Population: 10 million

Population density: 8.15 per km²

Population growth rate: 3.1 %

Capital: Bamako (pop.700 000)

Other main towns: Ségou (65 000), Mopti (52 000), Sikasso (50 000), Koutiala (37 000)

Languages: French (official language), Bambara, Peul, Shongoi, Tamashek

Curreny: CFA franc. In July 1996,1 ECU was worth CFAF 647.5 ($1 = CFAF 515)

Politics

Government: Mixed presidential and parliamentary system. Greater powers are due to be transferred to the regions after the next elections.

Head of State: Alpha Oumar Konaré

Prime Minister: Ibrahim Boubacar Keita Political parties represented in Parliament: ADEMA (absolute majority). 'Opposition' - CNID, USRDA and numerous other smaller groupings.

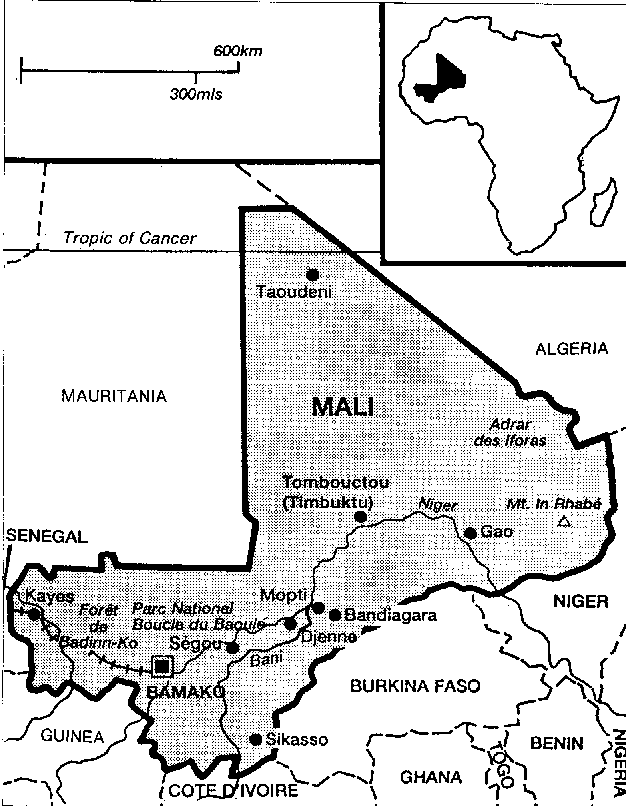

Map

Economy

(1993 figures unless otherwise stated) GDP: CFAF 753.8 billion

GDP per capita: $530

Origin of GDP by sector: agriculture 42%, industry 11 %, services 47%

Real GDP growth: 2.4%

Balance of payments: deficit of CFAF 84.1 billion (estimated)

Main trade partners (% of total trade)

Exports: Thailand (24.2%), Brazil (19.1%), Ireland (9.7%), Belgium/Luxembourg (9.7%)

Imports: Côte d'lvoire (22.2%), France (14.5%), Senegal (9.7%), Hong Kong (4.6%)

Main exports: cotton 40%, livestock 28%, gold 17.5%

Annual inflation rate: 3%

Social indicators

Life expectancy at birth: 46.2

Infant mortalityper 1000 live births: 158

Adult literacy: 28.4%

Enrolment in education (primary, secondary and tertiary): 16%

Human Development Index rating: 0.223 (171st out of 174)

Interview with Amadou Seydou Traoré, opposition leader and USRDA spokesman

'Macro-economic indicators tell you nothing about the distribution of the country's resources'

· It cannot be easy to be in opposition when Parliament is dominated by a majority which is given a good press and is regarded abroad as a good pupil.

-We do not really find it a problem. If one is familiar with Mali's current situation, the people's views, reactions and judgments count for more than outside opinion, despite the fact the latter may seem important. However, we do take account of others' opinions. We are pleased to be able to speak to you-to express our ideas and points of view- so that outsiders can see that the USRDA offers a credible alternative for Mali. We feel quite secure in our current position because the principles and values we stand for are those closest to the Malian people. So we have no problem in being the opposition party. We are not the kind of hysterical opposition which resorts to foul means as well as fair ones.

· Given that most Malian political trends stem from the revolutionary democratic movement, what are your party's special features ?

-Our party's origins are in the movement which dates from 26 March 1960-which itself grew out of an underground movement. The main component of this was the USRDA whose government was overthrown by a reactionary military putsch. Adema won the last elections, and we do not contest this fact despite a number of irregularities. Indeed, we supported the Adema government's initial actions. We were one of seven parties who regarded the Third Republic as our own offspring. Between 1992 and 1994, even when we faced grave difficulties and they were asking for suggestions, the government ignored our proposals. This happened, for example, at the time the World Bank threatened to pull out. As it functions at the moment, the government is not meeting the Malian people's basic aspirations. They want to see a change from the previous regime.

· What are your essential criticisms of the way Adema works ?

-We are critical on a number of fronts. Looking at it first from an institutional standpoint, when the Malian people rejected the old regime, they wanted the existing set-up to be changed into a democratic one. The few institutions that have been established since then do not reflect this desire. They are virtually no different from what we had under the single-party system. True, we have an opposition party, but its views are ignored. Second, in terms of the management of democracy, a number of bodies, such as the State Commission on the public media, simply do not function. You have been in Mali for a week now, so you must have heard Adema spokesmen on the TV or radio. But you will never hear a member of the opposition. The space reserved for that -formerly an open forum for free political discussion-has been removed and the state-controlled TV and radio stations do not allow political parties to have a say. In the economic sphere, our approach is also completely different. We believe that support for the development of the private sector means that the state has to act as regulator. Economic development cannot simply be left to run its course as a kind of 'rat race'.

· Could you give us a few practical examples of what you describe as Use selling-off of the family jewels ?

-With pleasure. Before the 26 March revolution, there was a general consensus that, in the process of privatisation, the state sector should be managed in a way that benefited the Malian economy. But the reality is that privatisation methods have not changed. They are no different from what they were in Moussa Traoré's time. The electricity sector, for example, which has not yet really been privatised, is now managed by the Bouyges group of France. And it costs more, which will hardly help the country's economic development. The state airline has simply been absorbed by Air Afrique.

· If you were in power, how much economic scope do you think you would have, given the prevailing trend towards international liberalisation ?

-I recognise that there is a dominant international lobby which has drawn up its own conditions, laws and principles. Even if one does not agree with this approach, one has to take it into account. However, it should be feasible to achieve privatisation in a different way. We know what we are talking about because we used to run this country. Indeed, we set up the national economy. Before 1960, there was no economic system to speak of. l am currently completing the text of a work which looks at our economic position at the time of independence. The plain fact is that we had nothing at the time of independence. There were only three pharmacists, fewer than ten doctors, and about ten people qualified to teach in our grammar schools-not much to write home about after 70 years of colonialism! After 1960, we had to set everything up from scratch. If you trace the history of every country in the world, whether under a monarchy or a republic, you see that the state has always made the first move in bringing about industrialisation, developing the maritime sector, and stimulating imports and exports. If you think about it, at the outset, the main manufactured activities were the domain of royalty.

· You claim that your party left a legacy, but some might say that the highly interventionist regime of your hero, Modibo Keita, who brought about independence, contained the seeds of Moussa Traore's dictatorship.

-These are just fairy stories. When a regime is overthrown by a coup d'etat, it always becomes the victim of systematic defamation campaigns in the press. We were maligned for 23 years with no right of reply and no right to issue a statement to set the record straight. In a way, we are talking today about a past which did not exist. You know the saying 'you are not only what you are but also what people say you are'. This reference to dictatorship is one of the most serious calumnies. But no matter what lies are told, something of the truth will always remain. If our regime had been dictatorial or inquisitorial, a coup d'etat would not have been possible. Before the 1968 coup, Modibo Keita was given a file by the security services warning him of the plot by Moussa Traore, and giving a list of his accomplices. He was advised to arrest the conspirators and put them on trial. His response was that he would not agree to a Malian citizen being deprived of his liberty without a scrap of evidence. I knew Keita very well. It will be a long time before we have another head of state with such democratic convictions.

· The ordinary people, the farmers, say that they did better under Traore, than under Keita.

-Yes, but it depends who you talk to. With Traore, there was an atmosphere of moral decline. We were free to plunder, steal and murder, but it was not real freedom. The farmers see it from a different perspective. However, l can still show you a copy of the 'Summary Report on the Seminar on Cooperation in the Rural Environment' which we drew up in 1968, just a few months before the coup d'etat. This highlighted the fact that socialism had not penetrated into the countryside during the seven or eight years we were in power. So you see our own self criticism appeared in a document published in May 1968. This demonstrates the fact that we were not complacent.

· What is your view of the compliments the current government is receiving from many foreign observers, and the good marks it has been given in the macro-economic field by international institutions ?

- Good macro-economic results which are due to good management of public finances are beneficial for the country. However, such management must be accompanied by greater welfare and an improved standard of living for the people. There is no point hailing a GDP increase of 3-4% if more than 10% of the population does not have enough to eat. You have been through Bamako and other towns and cities and you have seen the construction sites and big buildings. But in their daily life, people are now more ill at ease. They have been disappointed by the Adema regime. The welfare of the ordinary citizen cannot be defined by reference to the personal wealth of someone who is having a seven-storey building put up. All of this new construction is reflected in the higher GDP. But the macro-economic indicators tell you nothing about the distribution of the country's resources-and the scales are currently tipped towards injustice. Those who are working are earning less but those who do not work are earning more. Embezzlement and corruption are currently worse than under Moussa.

· What is the likelihood of a changeover of political power given that the opposition groups are at odds? The union between yourselves and Parena appears to have been suspended.

-We are capable of winning the forthcoming elections without entering into an agreement with any other party. Having said this, we are the party to which most groupings in Mali are now turning and we are currently in the process of forming an alliance which will carry a great deal of weight. l am not one to speculate but I am sure that Parena's supporters will, in time, reach the same conclusions as ourselves regarding the timeliness and suitability of an alliance between us. We have contacts with a number of other parties but we do not want to form an electoral pact in the way one would make preparations for a coup-forming a group, ousting the regime and then shooting at each other! Moreover, it is important not to confuse change with restoration. There are those who advocate the restoration of Moussa's regime. Opposition of that kind would suit the current government very well because it would allow them to raise the spectre of our former dictator in the hope of attracting support from those who are frightened by such a pro spect.

Interview by H.G.

The magnetism of the unfamiliar... but unexotic

In West Africa, there is a dry, desert-like region which a river tried to bring under its sway. Instead of flowing seawards, the river's path went in the opposite direction to find this region, impulsively tracing a majestic loop of 2000 kiLométres before heading seawards. The Niger may not have provided an ideal site for Mali's major towns and villages, but it was considerate enough to form a major waterway between them which is navigable over almost its entire course. Its network of tributaries has resulted in the formation of large landlocked lakes whose waters are full of fish-a reminder of the times when the Sahara was one huge expanse of water. It has also resulted in the extraordinary Niger basin, a central delta area the size of Belgium, criss-crossed by lesser tributaries which reach into the smallest valleys. The river has created a diverse landscape which entices the visitor back. The land is steeped in history and if one wishes to learn its secrets, one has no choice but to study the empires of the past, forged it is said, by mythological deities and heros.

During the dry season, visitors marvel at the beauty of the plains, which stretch as far as the eye can see. They will be tempted to return to view the waters that will cover them for just a few months during the rains. This is when the towns and villages appear as islands in the flooded landscape. Later in the seasonal cycle, Nature divests itself of its watery raiment and prepares to welcome the egrets, pink flamingos and all the other richly coloured birds which have flown in from afar. The cultural life of this region is also imbued with a rare richness, combining mystery and individuality. Mali has a distinctive character: it is accessible but not adulterated by frippery, welcoming but not taken over, affable but able to treat everyone as its equal. There is no need to make constant reference to the past which existed before colonial times-the past simply exists, eloquent in its tranquil humility.

A survey of Mali should logically begin in Bamako, the likely port of arrival. But if one immediately journeys to the towns and villages that were the cradles of empire, one is better able to appreciate this young capital, barely 250 years old, whose history owes much to its smaller forebears. We arrived in the evening and departed at dawn the next day. So Bamako was no more than a blur. The River Niger, still known as the Djoliba in the capital, is crossed by two long bridges which offer a view over the wild river banks. Most of the constructions are brand-new and some have a style borrowed from their thousandyear-old 'Sudanese' architectural heritage. It would have been more romantic to travel by river to the central part of the delta but, despite the welcoming nature of the Niger as it flows through Mali, it is difficult to navigate over the Sotuba rapids, between Bamako and Koulikoro approximately 50 km away. When the waters are in spate from July to December, it takes no more than two days to reach Segou, three to reach Mopti, five to reach Gao and an extra day to arrive in Timbuktu.

Segou, the rebel

Our first stop after Bamako is Koulikoro, the departure point for Niger cruises. After the unusual houses of the bazo fisherman on the banks of the river, as one leaves Bamako, it is the river itself which is a source of curiosity, transforming the voyage into a wonderful promenade through a forest abounding in game. Then there are the thatched, circular mud huts. Those without a roof are built on piles and are often ovens for preparing karite-nut oil whose bitter-sweet fragrance mingles with the fruity scent of the mango trees which line our route. In Koulikoro, every day is market day. The market spills out into the road and then shrinks back to allow vehicles to pass. It is also a centre for hunters and poachers who come here to seek customers. Above all, it is the centre for the guilds of masons who jealously guard the secrets of traditional Sudanese building skills. For the visitor who cares to linger, the griots will sing the praises of the old magician-king Soumangourou whose spirit has haunted this small town for eight-and-a-half centuries. When he was overthrown by the hero Soundjata, he just vanished into thin air-in the land of mystery that is Mali, great kings do not die, they simply disappear.

The first 250 kiLométres of the river's course from Bamako are enchanting. One's first real encounter with Mali's past come at Segou-when the balanzans come into view. The charming, independent city is close by. Segou, the Bambara capital, did not form part of most of Mali's empires. Indeed, the word Bambara comes from 'Ban-Mane', which means 'those who reject a master'. There are 4444 + 1 balanzans to announce the city, all of which are numbered except the last one, which still guards its secret. The balanzans conceal another secret: during the dry season they are covered with leaves, which they lose during the winter. A curious traveller might arrive at Segou with memories of Maryse Conde's fine prose (Segou, Robert Laffont, France, 1984). Her work is an epic fresco of life at the court of the Bambara kingdom in the nineteenth century. The city itself stretches for eight kiLométres along the river bank, with a promenade high above the river on an embankment from where there is an uninterrupted view over the water to the horizon. The richly coloured fabrics of the washer women create a dreamlike atmosphere, giving an impression of the shimmering tunics worn by princes, and the women who swim in the river are not given to excessive prudishness, another reminder of the city's enduring rebellious nature. The charm and cleanliness of the town are striking, its administrative buildings stretching along a grand boulevard lined with modern structures. We see in their profiles, the traditional architectural styles as well as a variety of colours. The whole scene is shaded by gardens full of flowers. It is easy to forget that Segou has retained none of its former architectural wealth. This was all destroyed by the organisers of a jihad who sacked this city of infidels who had never been won over to Islam or, later, to Catholicism. The city walls and the regal courtyards are all gone, so what remains is jealously protected: the sceptre and regal symbols of King Diarra, the kingdom's treasures and its secrets. On Mondays, market day, it is possible to see people kneeling at the feet of an old man. He is the custodian of the town's remaining riches, but will never reveal where they are held. Oumar Santara, one of Segou's intellectuals, is attempting to gain an insight into these mysteries in order to protect them better because, he says, the pillage is still going on. Mali's cultural heritage is being ransacked by outsiders. In some villages on the opposite bank of the river, it is still possible to find 13th-century coins in the village squares.

Trial marriage

Nearly 500 kiLométres separate Segou from Mopti. Midway between the two is San, barely more than a large village. San is bathed by the waters of the Bani, a major tributary of the Niger which it flows into it at Mopti. In the market, fine cotton fabrics can be bought, as can the skills of the blacksmiths. Here, however, there is above all an air of secrecy. The town's inhabitants are members of the Bobo people. The name translates es 'stammering', 'mute' being implied. This is the town which holds the secrets of fatal poisons- cocktails of poisonous plants and snake venom. There are also unguents of all kinds to relieve pain, alleviate scarring, and so on. San has another reputation, that of handing out severe punishment to adulteresses. This seems paradoxical when one discovers that women here enjoy exceptional sexual freedom during adolescence and up to the time of their marriage, and even afterwards. They enter into a trial marriage for three or four years, during which time they are free to 'play the field'. At the end of this period, on the occasion of a feast, they reveal whether or not they will accept their 'provisional' husband. If not, the woman regains her freedom and can start all over again as many times as she wishes. If she decides to become the man's wife, she chooses some of her husband's friends with whom she may 'have a fling' for two weeks, the aim being that she thereby lays to rest her unmarried freedom. She will then swear an oath of fidelity to her husband which she breaks on pain of being cast out of society and even, it would appear, at the risk of losing her life.

A 1 2-kiLométre dyke, which seems to float on the water during the winter season, links Sevare, the crossroads of the major routes across Mali, to Mopti. Situated below water level, Mopti owes its existence to the embankments which protect it. The dyke offers a fine promenade which opens out onto the quayside of this bustling town. The streets are crowded and the settlement has a vitality and beauty, with coloured lights mirrored in the water. On land, the crowds drift in much the same way as the multitude of boats anchored in staggered rows along the riverbank. These stretch for hundreds of metres- as far as the eye can see. All this wealth of detail forms a tableau punctuated by the outlines of the slender fishing smacks (pirogues or dugout canoes). Despite their size, these vessels retain their uncluttered lines, always giving the impression that they are slicing through the water. The biggest of them are perhaps 50 metres long, carrying cargoes of up to 150 tonnes. This strange, animated scene, which resembles no other in the world, seems to have been staged as a way of reviving the buried images of the Mali of legend-provoking a memory of things unseen and prompting new sensations. Despite the fact that it is replete with Malian influences, Mopti did not develop until colonial times. Like Segou, it never really belonged to any of Mali's great empires, although it became their meeting point. It is a place where all the country's languages are spoken. Indeed, the word 'mopte' in Peal means 'place of assembly'. At Zigui's restaurant or in a cafe down by the port, one find groups of beribboned Tuareg artisans still with their belle servants (former slaves) in tow. One can watch the Peals, also followed by their servants, negotiating their deals. Some trade in gold jewellery, dogon or other ethnic sculptures. Others buy and sell the magnificent Segou carpets or cotton fabrics. Others still dabble in ancient archaeological artifacts (which it is forbidden to sell) and in sacred objects from all over the country. The town itself is an artifact: the apparent hotchpotch is regulated by an internal, almost natural organisation. The hundreds of boats, fishing smacks and other small craft are arranged along the river banks according to the goods they are importing. There is one place for fishing boats, another for furniture imports, and so on.

Mopti merits an overnight stay. In the curve of the great arc which forms the port, a soft light lingers on the congested river banks. It is not just the people who seem to tire of the day's hustle and bustle. The biggest boats with their gentle backwash, anchored in the mud until the next incoming tide, grow too lazy for their images to be reflected in the water and they seem to hold on to the last of the sun's glow, awaiting the first glimmers of moonlight

The Dogon region, poetry in stone

As one approaches Bandiagara, on the threshold of the cliff faces which bear the name of this town, the landscape changes. Most of Mali is flat, but here, we find ourselves in the high land. In fact, the altitude is only a few hundred metres, but the landscape is dominated by sheer and rugged rock faces. This is Dogon country where everything seems to be made of stone: the roads, houses and hills appear in matching tones of salmon pink. The inhabitants, too, seem to have been hewn from the very rock. At first glance, the landscape is unremarkable apart from the sight of all this rock, but as one's perception grows keener, shapes can be made out. At the foot of the slopes are caves that are still lived in. And in the most vertical part of the cliff faces, we can pick out regular, sculpted barrel shapes, combining to form an impressive design. These stone cylinders are the ancient dwellings of the Telems, a mysterious people who preceded the Dogons and were conquered by them. Nothing is known about their disappearance. Today, the cylinders are used as Dogon graves. Access is gained to them during funeral services, by means of a system of ropes. At the top of the cliff is Shanga, the beauty of the Dogon region. It stands atop a 400metre sheer drop which extends over a length of 200 kiLométres. Reaching Shanga from Bandiagara involves picking one's way through the rocky landscape and sliding over sandstone scree.

Before the Europeans arrived to colonise the country, no one had succeeded in subjugating the Dogon region. Was it really ever under the sway of the colonists ? This region, whose beauty lies in its harshness, has no embellishments. And its language is as hard on the ears as the rock is underfoot. As everywhere, to feed themselves, the Dogons till the soil. But this must be carried on the backs of men and women over distances of several kiLométres and then deposited on the rock. Every onion bulb and every root pulled from this thin layer is a testament to the tenacity of humankind.

The Dogon region is like a magnet-it attracts pilgrims from afar who come to venerate El Hadj Oumar, the founder of the Islamic brotherhood of the African Tidjani-a military and religious leader whose life and disappearance are shrouded in mystery. It also attracts people because of the beauty of its works of art. Some of these, apparently of recent manufacture, are actually centuries old. For the custodians of the sacred objects, the interest of outsiders is viewed as a catastrophe. The artefacts are constantly pilfered and sometimes, their keepers commit suicide in their horror at such desecration.

Fine regalia

Djenne translates as 'the beloved of the waters' and is surrounded by two strekhes of the Bani river. Thus, apart from a short time in the dry season, when the river can be forded, it is an island accessible only by boat. The town has always been a rival of Timbuktu, the 'daughter' of the desert. Before Mopti was created, Djenne was the country's meeting point. The town is dominated by its mosque which is a masterpiece of Sudanese architecture. This imposing clay structure has been a magnet for the faithful since the thirteenth century. It has always been rebuilt in the same style, each version scrupulously identical to the previous one. The most recent reconstruction dates from the early 1900s.

Centre of the Malian empire, Djenne has retained all its finery, magnificence and prestige. It was annexed by the Shongoi empire at the end of the Middle Ages and its conquerors have always been seduced by the town's beauty. The mosque has been designated a World Heritage Site, and the entire town has protected status. For centuries, its architecture influenced other towns and cities in the Sahel and it continues to do so. The secrets of the knowledge and skills of its master masons are still jealously guarded, passed on only reluctantly to the initiated. The whole town is built around the mosque, revealing an interplay of balance and power. There are magnificent inner courtyards to which entry is gained through massive, ornate studded gates. The elaborate and finely carved windows, the intertwined leaves and scrolls of the arabesques and the moucharabies, all bear witness to the Moroccan influence. This has, however, been toned down and it now blends in with Djenne's indigenous forms of decoration and architecture. Whilst all Mali's former great towns and cities were known for their power and military glory, Djenne takes pride in having dispensed with brute force, its spirit protecting it from subjugation. All those who pass through take something of Djenne's spirit away with them.

Coca Cola kept at bay

Returning to the capital from where we started, we discover that it was colonisation that turned Bamako from a village into the large city that it is today. It inhabitants now number approximately one million. Although a city of recent origin, the site on which it is built dates back to the dawn of time. The hills overlooking the city are home to cave paintings and the underground tombs provide more evidence of a human presence dating from ancient times. There is then a gap of several thousand years in Bamako's history. In early colonial times, just two centuries ago, the village had no more than 700 inhabitants. Bamako began to be developed at the beginning of the 1900s and it is the only city in Mali to have a colonial atmosphere. It has not, however, lost out to change. The ministerial buildings at Koulouba hill, one of five dominating the city, or the Point G houses in the National Museum area, may not equal the beauty of Sudanese architecture, but they are elegant nonetheless. Their plain style is softened by their leafy gardens. The administrative buildings in the lower part of the city are often a fusion of colonial or modern styles and traditional architecture. These edifices are also made more attractive by fine gardens, which lend originality to the city. One of the most successful combinations is the great market, unfortunately in the process of restoration at the time of our visit and whose beautiful interior we were unable to appreciate. It is interior beauty which characterises this city in comparison with other African capitals. Despite its congestion and the density of its population, Bamako still has the atmosphere of a lively village. There is little of what one might term a 'social scene', but it is enough to be invited into the 'squares' or respectfully to visit the block-shaped houses which are still home to entire families and where discussion sessions (grins) last into the small hours. These sessions are enhanced with food and the omnipresent cup of tea. Bamako still prefers tea to imported beverages and to receive guests in the family home rather than joining in the social round in the hotel foyers so characteristic of major capital cities.

For those hesitant to venture into the traditional life of Bamako (although they would be assured of a welcome), there are many restaurants which make a good attempt at recreating a homely atmosphere. One is not, however, required to take part in the conversations. Two restaurants (the Djenne and the Santoro), which have opened recently, allow one to enjoy the pleasures of art and history. They are part of a wider project to promote Malian art and set up an organisation for artists and craftsmen. They contain areas modelled on the refinement of former imperial furnishing, interior design and architecture, as well as exhibits by Mali's greatest artists. Their creator, Aminata Traore, is an intellectual, art connoisseur and international expert. In Dakar or Abidjan, patrons of such establishments would probably be expatriates with perhaps a few local dignitaries. But at the Santoro and Djenne, prices have been kept reasonably low (no account having been taken of the 50% devaluation in the CFA franc) and the art remains accessible to middle-class Malians. Thus, the spirit of the 'grins' is preserved. The preferred beverage is still a cup of fragrant tea or perhaps a glass of refreshing juice. Whisky will never replace tea, nor will Coca Cola replace fruit juices. Mali is not a country which rejects other people, but it resists cultural encroachment, preferring the

familiar to the exotic.

Hegel Goutier

Mali-EU cooperation

Roads and adjustment

by Theo Hoorntje

For 1990-95, ECU 151.7m was allocated (mainly in project aid) under the seventh EDF National Indicative Programme (NIP). This is equivalent to about 1.5% of Mali's GDP and 13% of its public-sector investment programme for the period in question. European funds from sources other than the NIP-emergency aid, Stabex, European Investment Bank (EIB) venture capital and resources from the structural adjustment facility- reached ECU 87.2m over the same five-year period.

In 1995, support for the structural adjustment programme represented 5.4% of the balance of payments deficit and 7.8% of the budget deficit. Looking at all instruments together, the amount involved in financing decisions taken by the Commission last year was ECU 42m, with the disbursement figure rising to ECU 40m.

The NlP's primary commitment level under the 7th EDF rose from 76% at the beginning of the financial year to 92% at the end, which means that virtually all available programmable resources are now allocated to projects and programmes. The secondary commitment level, which involves the conversion of proposals into concrete agreements and contracts, rose from 33% to 45% by the end of the financial year. Disbursement rates remain relatively low (32% of available resources).

Allocations

Aid is distributed to the various sectors, as follows:

- Roads (29% of the total);

- Support for structural adjustment (20%);

- Rural development / Environment (1 4%);

- Support for the private sector (12%);

- Decentralisation (9%);

-Public health (9%);

-Water supplies (4%);

-Education/Culture (3%).

It is clear that Community aid concentrates mainly on road infrastructures-covering both maintenance and the opening-up of remote regions. Support for structural adjustment, which comes second, is used to finance the State budget's current expenses, particular emphasis being placed on improvement of fiscal and customs income and greater efficiency in health-policy matters.

In other areas, such as rural development, Community aid also makes an attempt to consolidate gains from previous actions, particularly through the development of rice growing and stock rearing, which should improve supplies to the domestic market and offer further export potential. As far as the environment is concerned, the aim is to contribute to the sustainable management of natural resources on the part of basic users, such as farmers, breeders, etc.

The private sector is supported by actions in key areas and by a programme that was recently set up which involves directing resources through a financial institution (Credit Initiative SA). The objective is to promote lending to SMEs, which is in keeping with the general aim of achieving economic growth.

In the context of administrative reform, priority is given to the decentralisation process which aims to promote the emergence of new local decision making centres (which should, in the long term, become key players in project development and implementation), and to give such decentralised bodies the means they require to fulfil these new public-sector missions.

As for health, Community aid has contributed to the PSPHR project financed by other donors. Its main focus is initially on infrastructures and on the policy relating to the supply of essential medicines.

In the water-supply sector, actions are aimed at strengthening village infrastructures, particularly in the Bankass and Koro areas. A solar-pump programme has also been set up in the Mopti and Koulikoro regions.

In addition to a school reconstruction programme in the north of the country, the Commission has been able to support education and culture through a dozen or so film projects.

Under the general 'heading' of non-programmable resources, there have been a number of interventions. These include extra support for structural adjustment, Stabex transfers, deployment of the balance from the 5th EDF and EIB projects. Emergency aid has been deployed in the north of the country where, despite difficult conditions, programmes have been able to continue without interruption.

Finally, Community regional aid is helping to combat rinderpest, as well as being directed towards road maintenance, and the provision of training and information on environmental protection.

T.H.

NGOs finally achieve tangible results

Catherine Beauraind and her five colleagues in the small team of foreigners and Malians, woke early. It had been a short night: our fault, since we had arrived at Bandiagara on the edge of the Niger valley much later than expected having taken the Sevare route. This is the gateway to the rocky Dogon region and travellers on the road occacionaliy fall victim to bandits-which probably made our hosts somewhat apprehensive about our late arrival. The people we had come to see are road builders, working without sophisticated equipment in a region of rocks and cliffs. They seem very youth froml, particularly those who have come from afar.

These are 'Progress Volunteers', the name given to the many young people who come to this very poor African country to offer their commitment and dynamism, if not perhaps their experience. On this particular morning, still feeling fatigued, Catherine was having to coordinate the departure of escorts for seasonal workers who were being dispatched to various locations. Their job is to ensure the upkeep of the rocky roads, and the equipment they use is rudimentary to say the least. The Bandiagara-Dourou stretch is maintained by the AFVP (French Association of Progress Volunteers) and is one in a long list of NGO projects. In 1995 alone, the European Commission supported over 50 NGO schemes, to the tune of ECU 1.5 million. Most EU countries and a number of others also have their own projects. On top of this, there is the emergency help provided by the European Commission Humanitarian Office (ECHO), which has just approved a grant of ECU 1 million for the north of Mali. Now that a peace accord has been signed between the government and the Tuareg rebels, this region is likely to see a huge influx of refugees returning to villages that are ill prepared to receive them.

Mali is a least-developed nation and one of the most highly subsidised countries in terms of per capita aid, though recently, its political fortunes have been boosted by the democratisation process. And the efforts of the NGOs now seem to be paying off. The recent times of famine have faded in people's memories even in the Dogon region, where many families ate calabashes in desperation before succumbing to starvation. Mother nature is playing a part in the country's renewal: there has been ample rain over the last Many NGO projects are aimed at helping the population use its meagre resources to exploit the natural wealth of the River Niger and its tributaries. At Konna, for example, a striking village at the confluence of two rivers, the Regional Literacy and Self-Management Project is up and running. Financed, among others, by the European Development Fund, this is being implemented at a number of localities, and it has played a part in the renewal which can now be seen. Fresh coats of paint, repairs to houses, fewer starving children and the return of many migrants all underline this new vitality. Each of the 17 small cultivated areas in the village that are covered by the project (worked by about 60 people), receives no more aid than a motorised pump, a few cereals and a small amount of cash in the first year. A basic course in management is also provided. It is up to the villagers to use these resources to yield a profit. Results tend to be good, proof of success being the growing number of such schemes which are being set up without aid from the organisation. The project is now in its seventh year. It did experience one bad year-1992-when, despite bumper harvests, rice imports into Mali were excessive and prices dropped. The village has therefore made an attempt to diversify its crops. Its objective is to sell onions in Cote d'lvoire, where the inhabitants are very fond of this vegetable.

Most villages have been able to save money which was initially placed in banks and then invested elsewhere in the wake of devaluation's harsh lessons. Konna opted for purchasing livestock. In nearby Kotaka, surpluses partially funded the construction of an impressive mosque. Kotaka was one of the places most affected by the recent meningitis epidemic, but a hospital would probably have been too expensive.

Hegel Goutier

Western Samoa

A new spirit of enterprise

Small countries with a limited resource base are frequently buffeted by economic forces over which they have no control. If you live in Western Samoa, however, you are likely to be preoccupied by forces of a different kind. For while most of the time, Mother Nature presents a benign face in this attractive and fertile Pacific state, every once in a while, she loses her temper.

Tropical storms are an unavoidable reality in much of the Pacific and they breed a special form of resilience which should impress the inhabitants of more temperate climes. The people of Samoa, and other cyclone prone countries in the region, are adept at picking themselves up and, if necessary, starting all over again, once the winds have passed. But between 1989 and 1993, the Samoans' capacity for renewal was to be tested more than ever before. Like a plucky boxer facing a much stronger opponent, the country would just be struggling back to its feet when another hammer blow would send it reeling.

The closest to a knock-out punch came in December 1991 in the shape of Cyclone Val-the worst storm to hit the islands in more than a century. This brought death and injury, as well as widespread economic devastation. The coconut and coffee trees on which the country depends for much of its export income were either swept away or stripped bare. Many homes were also destroyed and infrastructures were severely damaged. (The 1993 cyclone, although less powerful, caused further crop destruction.)

Over the last five years, virtually all the damage has been repaired. Indeed, a great many facilities have been upgraded with plans for further improvements in the pipeline. To some extent, the credit for this remarkable recovery must be shared. Overseas donors played an important part in restoring key infrastructures while expatriate Samoans, whose remittances are an important 'invisible' earning for the country in normal times, also rallied round. But the key players, of course, were the people themselves, who rose to the challenge of reconstructing their country.

Today, Western Samoa - which has a population of 165 000-is experiencing an economic mini-boom. Growth during 1996 is expected to be between 5% and 6% for the second consecutive year and there are encouraging signs of a new, home-grown entrepreneurial spirit. This is not to say that everything in the garden is rosy. The latest growth figures need to be set against the unavoidable recession caused by Cyclones Val and Ofa (which struck in 1990) and a mediocre economic performance throughout the 1980s. And while there is some evidence of diversification, the economy is still very narrowly based. There is also considerable room for improvements in health care and education provision. Doubts have been expressed, for example, as to the accuracy of the official literacy figures. Finally, there is a high level of dependence on foreign aid (the country's main donors are the Asian Development Bank, Japan, Australia and the European Community).

Economists will tell you how notoriously difficult it is to express the wealth of a developing nation in statistical form. GDP figures can offer a pointer, but they do not present the whole picture as they take no account of the informal economy. Western Samoa provides a particularly good illustration. At US $950, the estimated per capita GDP is very low by Pacific standards. Yet there is clearly no starvation. A great deal of the food consumed by the Samoans simply does not 'show up' in the cash economy. The term subsistence agriculture seems peculiarly inappropriate here since locally available food sources are many and varied.

Similarly, many of the materials used to build the 'fares' (traditional houses) in the villages are obtained without recourse to builders' merchants. And when a Samoan wants a new house, he builds it himself-with the help of his family and neighbours. This involves skilled carpentry work-for which people would pay highly in industrialised societies - and which does not register either in the country's economic statistics. So it is clear that the basic GDP figures do not paint a complete picture. Nonetheless, they illustrate the relatively underdeveloped state of the formal economy.

Agriculture

Looking at exports, Western Samoa's traditional agricultural sector has gone through some rough times, for a variety of reasons. In the past, the mainstays were copra and coconut products (oil and cream), cocoa and tarot

The storms destroyed or damaged many of the coconut and cocoa trees, wiping out exports for a number of years until new plantings could reach maturity. The market in food products derived from the coconut had been depressed in any case. One reason for this was negative publicity over the high cholesterol content of coconuts, although more recent research, suggesting that not all types of cholesterol are bad for you, has at least partly restored the reputation of this highly flexible crop.

Taro, which is Western Samoa's staple food crop, was exported in ever increasing quantities during the 1980s but the trade has suffered badly in recent years because of an outbreak of taro leaf blight.